The Land without Music

In 1904 the German music critic Oscar Schmitz levelled the charge that Great Britain was “the land without music”, and it was a charge with substance, at least as far as composition was concerned. Scarcely anything worthy of note had been produced by someone born in Britain since Henry Purcell, who died in 1695. There had of course been the towering figure of Georg Frideric Handel during the early 18th century, but he had been born in Halle (modern Germany) and was already a well-established and successful composer when he settled in London at the age of 27 in 1712.

There is also plenty of evidence that the British performed and enjoyed good music all through the “barren” period of the late 18th and early 19th centuries. However, they relied on overseas composers to bring the music to them. Notable examples are Mozart, Haydn and Mendelssohn.

Mozart’s visit was when he was still a child – although his first three symphonies were almost certainly composed in London – but Haydn made two highly successful visits and several of his best-known symphonies were composed wholly or in part when so doing.

Felix Mendelssohn made ten visits to England and/or Scotland between 1829 and 1847, and some of his best-known work (notably The Hebrides Overture and the Scottish Symphony) were inspired by his visits. His oratorio “Elijah” was commissioned by a Birmingham music festival and received its premiere in Birmingham Town Hall. His performances were always well received, not least by Queen Victoria.

However, that still left virtually nothing of worth having been written by home-grown composers.

Parry and Stanford

The Victorian musical renaissance was led mainly by Charles Hubert Parry (1848-1918) and Charles Villiers Stanford (1852-1924). Parry was more of a theorist and Stanford the more accomplished musician.

Parry was thoroughly English (born in Bournemouth) but Stanford was born in Dublin and only came to England when admitted to Cambridge University at the age of 18. Ireland was part of the United Kingdom during the 19th century, so he was always a UK subject.

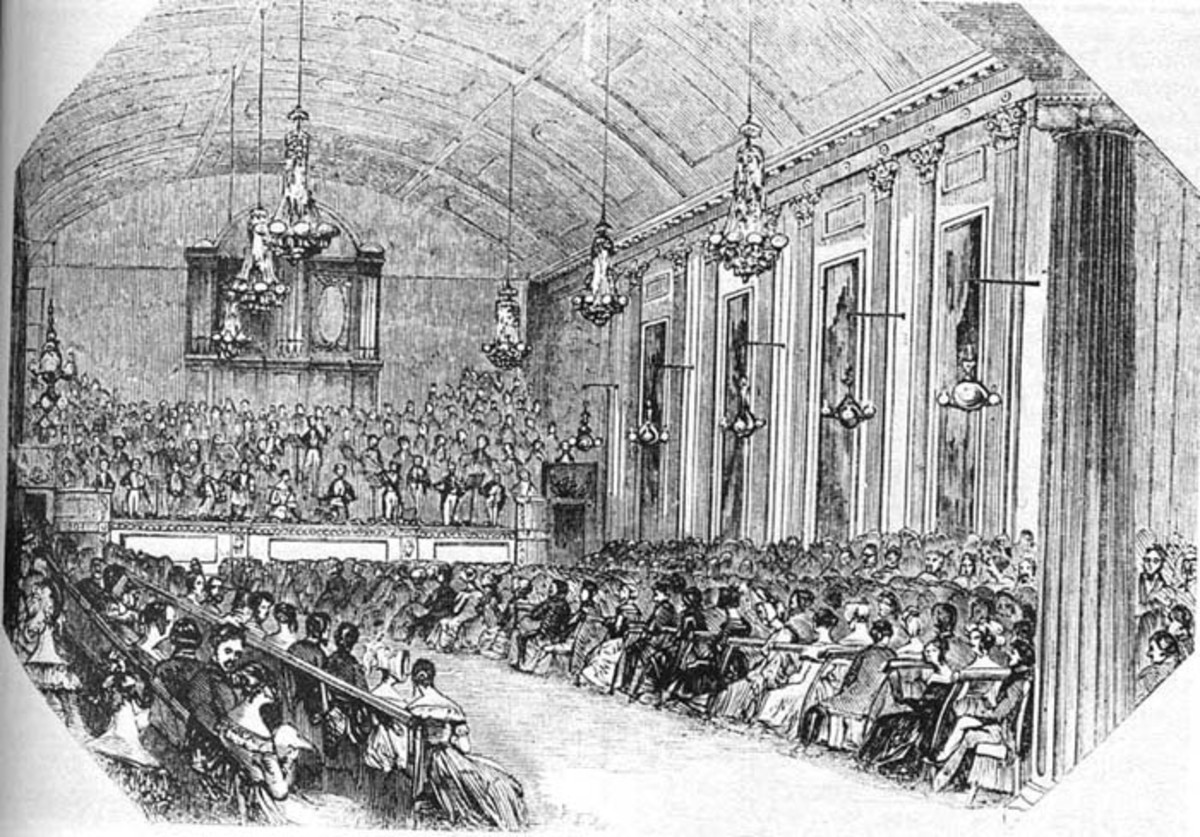

Both composers adopted the idea of setting to music the poetry of great English writers and composing pieces that were well suited to performance by choirs and choruses, thus taking advantage of the English choral tradition that had long been fostered by well-established cathedral choirs and had found its way out of cathedrals into amateur and professional choral societies that regularly performed such works as Handel’s “Messiah” and Mendelssohn’s “Elijah”, mentioned above.

Parry made a great impression with his 1880 setting of Shelley’s “Prometheus Unbound”, and in 1886 Stanford set Tennyson’s “Revenge” to music. Parry wrote some highly successful oratorios, such as “Job” and “Judith”, and his choral odes “I Was Glad” and “Blest Pair of Sirens” are still performed regularly. He is probably best known as the composer of the tune of "Jerusalem" ("And Did Those Feet ...").

Stanford was also notable for composing the first full-length British symphonies, completing seven in total.

The Royal College of Music

Parry and Stanford were both leading lights in the Royal College of Music, which was founded in London in 1882 with the aim of providing a rigorous grounding in the basics of both composition and performance. One of its basic ideas was that budding composers would be able to try out their pieces by having them performed by well-trained and competent orchestral musicians.

Parry and Stanford both served as professors of composition at the RCM, with Parry being the college’s Director from 1894 up to his death in 1918. It is entirely possible that these two pioneers would have developed even further as composers had they not devoted so much energy to teaching.

Composers who benefitted from the tuition of Parry and Stanford at the RCM included Ralph Vaughan Williams, Gustav Holst, Samuel Coleridge-Taylor and John Ireland. These men would form the nucleus of the next generation of British composers who would build on the start that Parry, Stanford and others had given them.

It would be a mistake to give Parry and Stanford all the credit for the musical renaissance that took place in late Victorian Britain. The RCM was the brainchild of others, most notably Sir George Grove (the founding editor of “Grove’s Dictionary of Music and Musicians”). There was also another well-established musical institution in London, namely the Royal Academy of Music that opened its doors in 1822, but this had concentrated on performance rather than composition and did not have the emphasis on professional musicianship that the RCM was to engender.

Sir Edward Elgar

To the general public, no composer better represents the revival of British music during this period than Sir Edward Elgar (1857-1934), famed for works such the “Pomp and Circumstance Marches”, “Enigma Variations”, “The Dream of Gerontius” and much-loved concertos for violin and cello.

There can be no doubt that Elgar was a far greater composer than either Parry or Stanford. However, Elgar was very much an “outsider” in terms of the work that those two composers were doing. His base was his home county of Worcestershire, but his musical education was from the continent of Europe and his skills as a composer were largely self-taught.

Elgar fused the Wagnerian and Brahmsian influences that were then coursing through European music with impressions gleaned from Liszt, Verdi and Strauss.

However, although universally beloved in England, Elgar’s music has never been as widely appreciated by audiences elsewhere. This may in part be because Elgar was every bit as enamoured of the English choral tradition as were Parry and Stanford. He made his name as a champion of the Three Choirs Festival, which showcased the cathedral choirs of Worcester, Gloucester and Hereford Cathedrals, writing anthems and oratorios intended for an ecclesiastical setting.

With the exception of “The Dream of Gerontius”, it is Elgar’s instrumental music that is more often heard today, and which is regarded by most hearers as being quintessentially British, which is ironic given the strong Germanic influences on the composer’s musical background.

A Firm Foundation

The three composers mentioned above lit the fuse for an outpouring of musical composition in Great Britain. Apart from the early products of the Royal College of Music referred to earlier, mention should also be made of Frederick Delius (1862-1934), Herbert Howells (1892-1983), Gerald Finzi (1901-56) and William Walton (1902-83). The accusation of Britain being a land without music could not possibly have been levelled at any time since it first ceased to be a gross inaccuracy.

© John Welford